Farmed Fur

The Truth About Farmed Fur in North America

The farming of mink was pioneered in the USA more than 150 years ago, during the Civil War, at Lake Casadacka, New York. The first attempts to raise mink in Canada were recorded in the 1870s, by the Patterson Brothers, in Richmond Hill, Ontario.

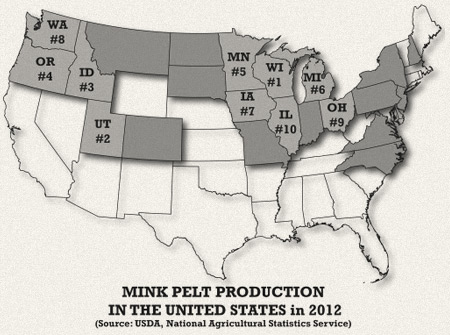

USA: Today, some 275 mink farms in 23 states across the USA produce about 3 million pelts annually, with a farm-gate value of more than $300 million USD (2013). Wisconsin is the leading mink-producing state, generating well over 1 million pelts. Other important producers are Utah, Idaho, Oregon and Minnesota.

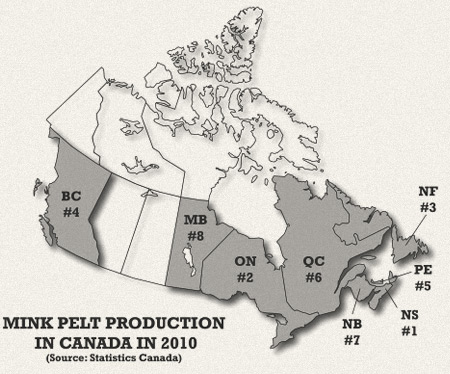

Canada: There are currently some 300 mink farms in Canada producing more than 2.8 million pelts annually worth $280 million CAD (2013). About half of these mink are raised in Nova Scotia. Other important producers are Ontario, British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Quebec.

Mink belong to the biological order carnivora, or meat-eaters. Within this order, mink belong to the family mustelidae (animals with scent glands), a group of efficient predators that includes skunks, martens, ferrets, fishers, wolverines and other members of the weasel family.

American mink (the species both raised on farms and found in the wild in North America) are classified as Mustela vison or Neovison vison.

Through selective breeding over more than a century, North American farmers have developed a wide range of beautiful fur colors. Farmed mink are, in fact, quite different than their wild cousins. They are considerably larger and tamer.

From an ecological perspective, fur farming plays an important role in completing the agricultural nutrient cycle:

In other words, farmed mink recycle nutrients that would otherwise clog landfills, while producing a wide range of valuable natural products.

Although the basic activities which focus on providing the mink with a comfortable and stress-free environment, clean water, well balanced diets, and overall good health, remain the same year round, many other activities change based on the season, and where the mink is in its life cycle. There are four main seasons on a mink farm:

Mink are brought into good breeding condition. Diet and feeding program adjusted to remove excess weight and encourage increased exercise. This is important for good production and a successful whelp.

Some ranches choose to blood test (Aleutian disease) or vaccinate at this time.

Mink are positioned in barns depending on the breeding system practiced. This often involves small sections of male mink surrounded by larger sections of female mink. Most farms breed a ratio of 4-5 females for every male.

Females are always placed into the males’ pens for breeding – never the reverse – as the males should remain on their own territory.

The act of mating stimulates ovulation. This is similar to domestic cats but different from other domestic species. At 9 days after the first pairing, the ovaries have been replenished. Thus, most ranchers practice a breeding program of Day 1 and Day 9. Many ranchers also mate the day after Day 9 (Day 10), as they feel that the extra mating results in the fertilization of more eggs.

Breeding records are often kept for tracking the mating dates, but also the genetics of parents, grandparents, etc., and selection information.

The farm-raising of foxes began in the 1880s in Prince Edward Island, Canada, when fur industry pioneers Sir Charles Dalton and Robert Oulton began raising fox pups they obtained from the wild.

Through countless generations of selective breeding for color, size, quality of fur, fecundity, docility, mothering ability, growth rate, and litter survival, the farm-raised fox has evolved to be very different from its wild counterpart. Good nutrition, veterinary care, and adequate, secure accommodations have resulted in a larger, more robust animal exhibiting a much quieter temperament.

Most farmed foxes are fed with commercially manufactured, dry pelleted feed similar to pet food. Many are fed with a diet made up of fish and meat packing house by-products and other “food wastes”, supplemented with a grain cereal, vitamins and minerals, just like farmed mink.

Modern day fox production in North America is quite small in comparison to mink. Today, Finland is the world's leading producer of fox pelts; with Canada producing ten to fifteen times as many fox furs as the USA.

The Chinchilla has been prized for its luxuriously soft fur since the arrival of Europeans in South America. One of the defining features of this luxurious fur is its remarkably soft and velvety texture. This effect is caused by more than 80 individual fibers growing from each hair follicle (in contrast to most animals which produce just one hair per follicle).

The indigenous populations of the Andes were using chinchilla pelts more than 1000 years ago. The name chinchilla -- which was given by Spaniards who arrived in Chile in 1524 -- is believed to be a reference to the local “Chincha” people.

Wild chinchillas were trapped in large numbers, almost to extinction, in the 1890s and early 1900s. To preserve remaining populations, trapping was prohibited by the Chilean government in 1910 and the first attempts were made to rear chinchilla in captivity.

Mining engineer Mathias F. Chapman exported eleven live animals to the USA in 1922-23. The present farm populations of chinchilla derive almost exclusively from these first few specimens of Chinchilla laniger. Chinchilla are now raised commercially in North and South America, and in several regions of Europe (e.g., Hungary).

After furs are harvested on the farm, they are usually sent for sale at one of North America’s leading Auction Houses.

About half the fur pelts produced in North America (and as much as 85 percent worldwide) now come from mink and fox farms.

Wisconsin is the most important mink producing state in the USA, generating well over 1 million pelts per year. Other leading mink-producing states include Utah, Idaho, Oregon and Minnesota.

With over 120 farms and 1,000 workers, mink farming is Nova Scotia’s largest agricultural activity and accounts for half of Canada’s total mink production. Other important mink-producing provinces include Ontario, Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, British Columbia, and Quebec.

North America produces about 10-12% of the annual world production of farmed mink (i.e., about 6 million pelts of total global production of 50-60 million pelts. Europe is the most important farmed-fur producing region, with Denmark alone raising about 13 million mink pelts.

While not the largest producers, North American farmers raise some of the highest quality farmed mink and fox in the world.